In AI, 2025 is a year for strategic clarity. We can finally part the fog of war and glimpse where this technology is headed, how companies & governments are likely to react to it, and how you, dear reader, should think about its effects on your life and work.

In this essay, the first of two on AI’s path forward this year, I explain some of my guesses for where AI development is going in 2025, using a dense set of heuristics and mental models that I hope are particularly useful for those who work in AI policy.

I argue for several framings that are key to predicting future developments:

AI will eventually diffuse widely. Costs are falling extremely rapidly, and distillation and compression are powerful. It will simply not be very expensive, in 2030 $, to make AGI.

Reasoning model progress is driven by repeated iteration in domains with verifiable or close to verifiable reward. The number of domains can be expanded over time to achieve wide coverage. This is complemented by periodic scaling up of pretraining.

“The model does the eval”—models are good at things which we can build evals for, and poor at things for which we struggle. However, building evals becomes easier with more capable models.

Agents are key to economic effects, not chatbots, but they are expensive to run! On current trends, there will be a “capabilities overhang” for a few years, with significantly more demand for compute than can be met globally.

An easy way to measure the abilities of AI agents is their time horizon—the length of time they can act autonomously and reliably. The reliable time horizon of frontier AI agents will be significantly ahead of others, but given enough time even open source agents will be able to act as a “drop in remote worker”.

The “automated researcher” is possible, and we should expect them to significantly accelerate progress over the next few years.

“How did you go bankrupt?” Bill asked.

“Two ways,” Mike said. “Gradually and then suddenly.”

Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises

Tick-tock?

In the midst of a chaotic information environment, I think it’s worth stepping back to reflect upon how far we’ve come and consider the current drivers of AI progress. Throughout 2023 and into late 2024, we have seen the steady development of language models into AI chatbots, as they become more and more integrated into our daily lives. We use them as search tools, as writing assistants, but also increasingly for advice, counsel, and as a brain partner.

We are now moving into a new, even more rapid phase of AI development, focused on autonomous AI agents and reasoning models. The term “agent” is overhyped, but the core concept is still valuable: an autonomous system that can take actions over many steps to achieve its goals, without needing direct supervision. In today’s context, this increasingly means actions on the internet or in a coding environment.

The main engine of this new rush in progress is the breakthrough, years in the making, of the ability to get AI models to think reliably for longer periods of time, reasoning their way to a better answer. We first saw true inference-time scaling with OpenAI’s o1 release, although researchers had been trying to make variations work for years prior. DeepSeek’s r1 paper lifts the veil from the core research idea: using reinforcement learning on LLMs, with rewards on the outcome of tasks with verifiably correct answers, will automatically teach the models to error correct, generate hypotheses, check their work, and reason towards a final answer. “Unhobbling” has arrived in earnest.

A real piece of magic here is that the model’s learned reasoning heuristics—the ability to consider an idea, then backtrack and reconsider upon gaining further information—generalize outside of the domains it was trained on. You can ask DeepSeek’s r1 to write you a story, and its chain of thought will follow similar patterns, despite clearly not being trained with RL to write stories.

This generalization shows a tantalizing path forward to further, self-reinforcing, advances in AI’s capabilities. Of course, to some extent these will still depend on the ability to verify the correctness of an answer, and get reward for the RL training process. Many commentators have pointed out that this may significantly limit the potential of reasoning models in the short term, because only a relatively narrow range of tasks have exact and cheap verification.

But very often, verification need not be exact! There are a surprising number of ways to obtain proxy rewards with a combination of specialized models, heuristics, and format specifications, even in relatively open-ended domains like legal writing or navigating web pages. These are domains with pseudo-verifiers. For many web browsing or enterprise software navigation tasks, synthetic environments and rollouts can be generated which are sufficiently realistic (consider that a huge portion of white collar work simply occurs in Google Docs, Office, Gmail/Outlook, and Slack). Researchers must be cautious, of course, to not Goodhart or over-optimize models for these proxy rewards, causing worse performance in the real world. And using a pure LLM reward model as a verifier without any grounding will usually fail to scale. But often, the implicit gap between the difficulty of verification and the difficulty of generation will be sufficient to progress in important domains.

In hindsight, perhaps it’s not surprising that this works so well. Previous attempts to get models to reason their way through complex problems often depended on supervising the correctness of each step of reasoning—process-based supervision. But especially for large and complex tasks, why should we expect models to follow the same reasoning process as humans? AI models have non-smooth skill distributions: in contrast to humans, we cannot reliably predict how capable an AI model will be on closely related tasks. This property is improving as models get better and more robust, but there are still, for example, many types of problems for which GPT-4o is worse than a nominally weaker competitor, or where performance varies drastically based on minor prompt differences. As a result, the model designer should not try and force the models down a reasoning path that is most natural for humans. Instead, let the model figure out for itself the best path to solve the problem: give them a goal and let them run. The models just wanna learn.

In parallel to advances in reasoning (and post-training), we also expect improvements via scaling up pretraining. Grok 3 and particularly GPT-4.5 are the early signs of this—GPT-4.5 is clearly a much bigger model, but it hasn’t received significant RL fine tuning for reasoning, so is most clearly comparable to GPT-4 to see the effects of scale. And what do we see? The public benchmarks are relatively underwhelming (mostly due to saturation), but the model topped the Chatbot arena and qualitatively seems to be an extremely good model, with some users reporting that they prefer it for common coding questions.

Overall, development seems to be trending towards a “tick-tock” model, in which pre-training scale-ups every few years are complemented by increasingly fast progress in continually finetuning the models using RL across a spread of verifiable or pseudo-verifiable domains.

Significant efficiency improvements are also being driven by the power of distillation. As researchers train larger and more capable models with each generation, they can use them to generate data and reward signals to train smaller, more compressed, cheaper models which retain much of the original capability. The abilities of the small Gemma 3 models would have shocked the AI researchers of 2021. The fact that such strong capabilities are possible in so few weights is a powerful hint from the universe that many components of human intelligence are just not that complex, and that this technology is ultimately destined to proliferate cheaply.

These factors drive the widespread, albeit lagged, capability diffusion of AI into smaller and cheaper models over time, including those created by non-frontier AI labs. Because larger models tend to be more capable, and yet more expensive to run, AI labs are increasingly incentivized to follow a scheme of “train large strong model, distill into smaller cheap model”, as seen with Gemini 2.0 and o3-mini. Wide deployment then ends up being limited largely by the effectiveness of distillation and compression.

So far, we have seen distillation (and other algorithmic advances) improve over time, to the point that small models can continually increase in performance despite not changing in size. For economically useful tasks, models at the frontier are still markedly more valuable than their smaller, less capable cousins. But most tasks which are highly valuable have a fixed “difficulty”—at some point, due to distillation and compute improvements, models of a fixed low $/token price will be capable of automating the work of e.g. a junior investment bank analyst, whilst the most capable models will still be struggling to complete much higher complexity tasks. This dynamic will likely continue until the vast majority of economically valuable tasks can be cheaply automated, even if it takes some time to convert the models from expensive to cheap—although many difficulties remain, especially around tasks which are harder to verify or build good environments for.

Finally, in the bigger picture, all the progress we have seen so far is a result of the effort put into building better and better evaluations for capabilities. Anything we can robustly quantify, we can turn into a benchmark—and then the model does the eval. In the long term, this means that we should expect AI models to do well on almost anything we can specify and quantify, and poorly in things we struggle to define rigorously, like top 0.1% fiction writing ability.

The Automated Researcher Dream

A huge driver of progress, still underestimated, is the advent of AI agents capable of AI research: automated researchers. The frontier AI labs are racing fast towards end-to-end AI R&D agents. They know that once this capability is achieved, progress could be made with much greater velocity, potentially in a self-reinforcing loop—newly discovered algorithmic advances themselves helping to bring the next breakthroughs closer. The best AI researchers in the world are rushing headlong into a grand project to automate their own jobs. Indeed, there are rumors that within Anthropic, some researchers have raised concerns to management that their jobs could be at risk.

Of course, AI safety advocates have many concerns over this: it may be harder to supervise in some way—how could we tell whether our automated researcher is capable of robustly evaluating the latest, more capable AI model? This problem, known as scalable oversight, has long been a reason for some to argue against building superhuman AI systems. But I’m more optimistic: the advent of inference-time compute scaling implies that the scalable oversight problem is potentially solvable by simply providing more compute to the supervisor or evaluator model.

However, automated research has more difficulties than meets the eye. First, most AI lab research teams are compute bottlenecked for their experiments, and are limited to some GPU allocation handed down from on high. Researchers are strongly encouraged to use all of their compute, and typically have far more useful experiment ideas than they can carry out, even if they somehow coded them up instantly. To achieve significantly better utilization of a compute budget and thus faster research, automated researchers need to have better ideas than the average frontier AI lab researcher: quite unlikely, at least in the short term.

That leaves the other parts of the research loop, most prominently engineering: coding up new research ideas and developing faster or more efficient infrastructure. Significant parts of frontier AI lab workflows are bottlenecked on simple implementation speed and testable software improvements (e.g., CUDA kernels), and this looks much more tractable for the first automated researchers to tackle. I believe that automated researchers are likely to provide a large boost here, but it may be effectively a one-time boost to overall research speed without improvements in the other parts of the research loop.

Overall then, the incentives are strong for AI labs to race towards capable automated researchers. Attaining this capability means that labs are less talent constrained: it enables a pure conversion of compute into intellectual effort, and implies that even labs which struggle to attract talent are guaranteed at least some baseline of research ability, provided they can obtain a good enough starting model.

However, the biggest unanswered question is still that we don’t know how fast the automated researcher feedback loops will run. Will we get a modest “one and done” bump in the short-term from automating engineering, or will the self-reinforcing feedback loop be so strong that we unlock significantly more capable automated researchers in short order? To some extent this is a fundamental question about the difficulty of AI research itself, and whether the marginal research secret (or “micro-Nobel”) becomes easier or harder to obtain over time, if you are continually improving at research ability. Regardless, we will likely find out the answer soon: I currently believe leading AI labs are on track to have the first fully automated researcher prototypes by the end of 2025.

An AI research ecosystem with a dramatically larger capability differential between labs only ~6 months apart in progress may have interestingly destabilising effects. As new capabilities appear even quicker, new implications for economic growth and national security are unlocked with even less time for companies and governments to react. Currently, the speed of automated research is set to be closely guarded by AI labs—I think that reporting some statistics about this to say, the Office of Science and Technology Policy in the U.S. government could help improve decision making significantly in the future.

Agents and their Effects

I’ve been playing with Deep Research and Operator for several weeks now, and I’m convinced: these systems1 are our first glimpse at the agents of the future. They have an unprecedented degree of coherence and reliability over long time horizons, despite many rough edges. It’s often captivating to see these models generate tens or even hundreds of thousands of tokens of reasoning before giving their final answer.

However, there are still many issues to overcome as this new form-factor develops. Agents operating within a browser have key limitations on a technical side: reliability (which has noticeably increased, driven by dataset improvements), visual understanding (for operator-like agents), planning capability for high level tasks, and familiarity with key common apps and websites. This last one is grounds for optimism about the speed of economically-relevant development: since vast quantities of office work takes place essentially within a handful of apps (Google Suite, Office, GMail, Slack, etc), it should be possible to vastly increase the reliability of agents in these specific apps by creating handmade training environments for each.

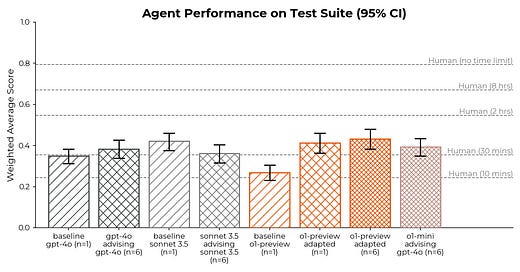

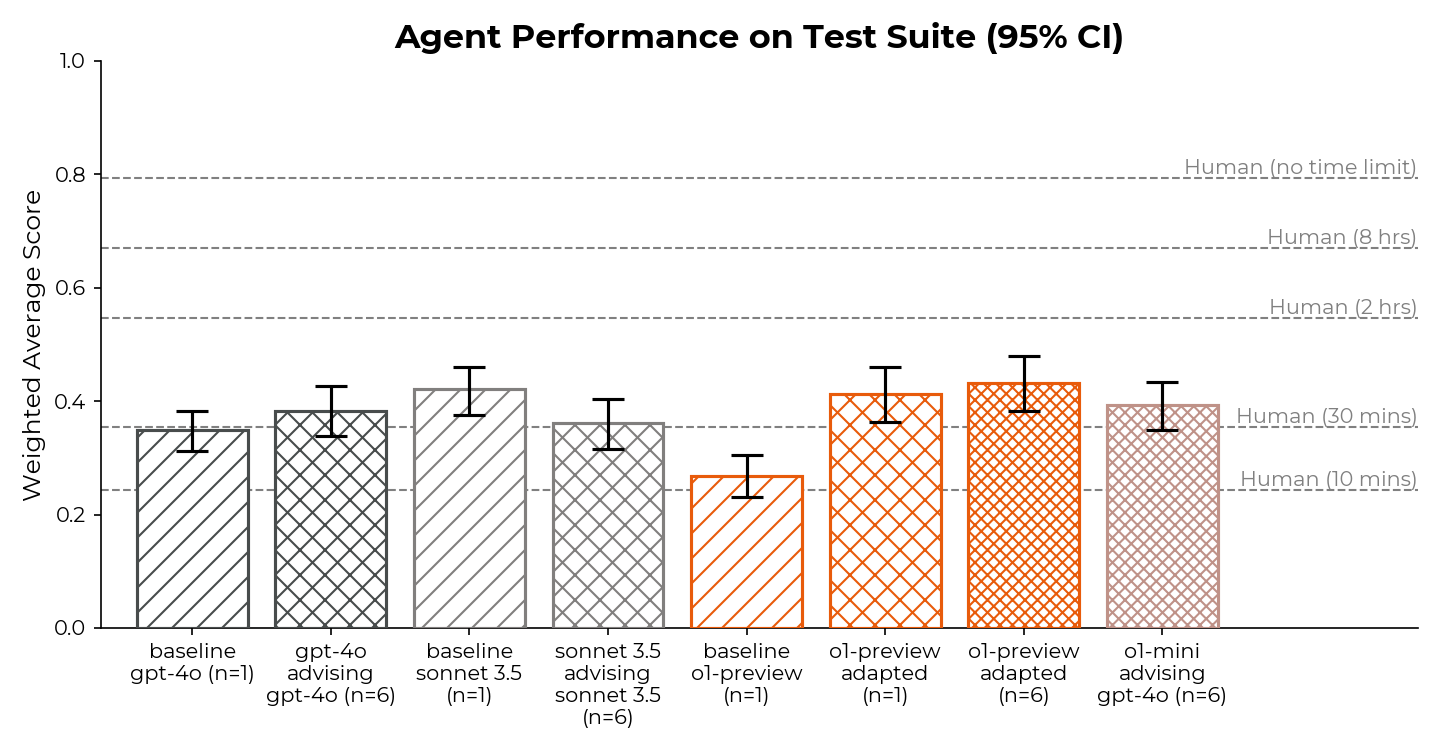

There is a framework for describing progress here which I quite like, called t-AGI. If we take AGI to mean the “drop-in remote worker” imagined by many AI lab leaders, the idea of t-AGI is that we should, before full AGI, expect to have systems capable of acting like a drop-in remote worker for time-bounded tasks that would take an expert human, say, 30 minutes. Then, upon further development, the AI system will become capable of 2 hour tasks, and so on. We should also consider the probability of success: the system may be capable of the average 30 minute task with an 80% chance of success, and we can plot the progress over time at a fixed success rate.

But this is too low-resolution, since we know that AI capabilities are spiky! Models which can reliably code features that would take an expert software engineer 2 hours may struggle terribly to do things that a junior consultant or physicist can do in 10 minutes. Of course, there is some amount of general capability transfer, and in many ways AI progress for the past few years has had the effect of making things less spiky. But overall, I currently prefer to refer to t-AI, not t-AGI, and describe things in specific but broad domains.

We already see this t-AI dynamic with agents to some degree, especially in areas easier to evaluate like software engineering and AI research (as shown by METR). I currently think we have AIs averaging 80% reliability at a broad sweep of 10 minute tasks, though the time horizon is probably closer to 30 minutes or longer for specific domains like software engineering and compiling basic research reports from the web—and longer still for 50% reliability. I expect these time horizons to extend to ~8-12h by mid 2026, and a full day by 2027.2

We also see it with Operator and Anthropic’s computer-use agents, which can often reliably complete web browsing tasks of short duration (e.g., 1-10 minutes) but which struggle to continue the more actions are required. I expect this increase in t, for many domains, to be one of the biggest factors underlying the development of economically useful models. Deep Research is currently a leading indicator of this—the model is capable of searching over the web up to ~30 minutes in duration, before compiling a report about its findings.

Operator inherently delegates authority to humans for some actions which are particularly important or sensitive. This functions as an implicit "decision threshold", a quality that is partially social and cultural, which we can expect to rise over time as the system proves its reliability & trustworthiness. Eventually, this threshold may be high enough for contracting or managing workers, making major purchases, sending critical emails, and more. The autonomous corporation beckons?

Compute Bottlenecks

Now, suppose an AI company develops a 60m-AI agent for many tasks common in the professional workplace, including software engineering, producing, analyzing, and reviewing reports & slide decks using publicly available information, drafting or editing articles or papers, and so on—tasks chosen because they appear to be amongst the easiest to automate with current technology. This AI agent would be immediately extremely valuable to many businesses—but how many businesses would actually be able to run it? Do we have enough compute for widespread economic benefits? Indeed, labs have shown some indications that reasoning agents are strongly compute constrained: even paying for OpenAI’s pro $200 subscription only gives you 120 Deep Research queries per month.

Assuming that this 60m-AI agent might be based on a model of similar size to DeepSeek’s r1 (or indeed larger), then it requires at least a full set of 8xGH200 GPUs to run. This is the size of NVIDIA’s latest AI server, costing $300k. Some basic napkin math shows that OpenAI’s announced Stargate project could sustain running at least ~3.1 million of these agents 24/7 by 2029 for a cost of $500b, (albeit not counting batching, so a very loose lower bound).

In 2025, the approximate existing stock of NVIDIA H100s in the US could sustain, on similar assumptions, at least ~125k agents. If we assume distillation and model compression improves on trend, this capability could eventually fit onto a single chip, making the numbers ~25m and ~1m respectively (let me know in the comments if you have better numbers!). The excellent

provides some similar numbers for the long-term estimate (on a single chip) via a different route.These are not huge numbers, especially if models grow to be capable of automating large portions of work in many professional sectors. Similar calculations may be driving some of Sam Altman’s desire to build Stargate. Of course, there are many other factors in inference economics which could both alleviate or increase this potential bottleneck. For example, distillation will continue to be strong (enabling older GPUs to be used at scale), inference runs well on older GPUs or alternative chip providers, other algorithmic factors like batch sizes, parallelism, and token speed will likely improve, and adoption is set to be slow throughout many sectors even after the technology exists. On the other hand,if pretrained model size needs to be scaled significantly to achieve high reliability, the inherent inefficiency of serving large models (see GPT-4.5 token costs) may delay large-scale use of effective agents for some time. We also have yet to explore how useful it will be to run many agents in parallel for a given task—perhaps the best configuration consists of a swarm of agents completing different subtasks? And what new forms of work may be enabled by the existence of these agents?

Conclusion

Overall, I expect AI agents to be very compute bottlenecked in the next couple of years, largely because of the sheer speed of progress creating an “economic overhang” of sorts. By the time we have 24h AI agents for many common tasks—perhaps mid to late 2026—most data center projects currently planned & approved will be nearing completion. Other infrastructure is not so speedy, and things like energy and power transmission construction have significantly longer lead times. At some point, progress (and importantly, economic adoption) may slow down due to fundamental constraints on the availability & cost of chips or energy.

A large compute supply bottleneck will create new (temporary) political and economic dilemmas for both AI labs and governments. Should compute be preferentially allocated to companies, academic researchers, and other groups, to satisfy the interests of both the public and AI developers? As we move towards capable autonomous scientific researchers, can governments use their compute to accelerate key public interest research projects in many domains of science?

Longer term however, there is plenty of light at the end of the tunnel, driven by the combination of increased AI chip production and efficiency improvements for a fixed level of capabilities. Eventually, I expect t-AGI for most common workplace tasks3 to be at a level of capability distillable into fairly cheap models, which will greatly decrease the compute requirements and potentially unlock t-AI on consumer devices.4 Ultimately, I believe the cost of intelligence will tend towards zero.

This is the first of two big picture essays bringing together my views on AI progress and where we are headed. The second part, coming soon, discusses the implications of this AI progress for the economy and geopolitics. I will argue that in the context of the US-China competition, AI should be viewed as a form of raw economic advantage, with compute as the key lever that the US can use to secure this advantage.

See: Gemini Deep Research, Operator, OpenAI Deep Research, Manus, etc.

Estimates compiled from dozens of conversations with lab researchers as well as soon-to-be-released research by METR

Note that this is specifically for the current, 2025 distribution of tasks in the workplace. I expect this distribution to change rapidly if automation is rapid—making AGI a target that continually moves further away, by some definitions.

Apple is set to be a big winner of this dynamic as long as they can rescue Apple Intelligence.

This essay is great. My challenge is whether it's over fit to the last few months of progress. It seems very anchored on inference-time compute but that wouldn't have been the focus 6 months ago. Is it reasonable to think that this will remain the important axis for scaling for more than a year or two?

The idea of looking at task completion % for tasks of set lengths (10min, 30, 2h) is a great idea and would be a very useful eval to keep people's expectations grounded. Reminds me of Anthopic demonstrating Claude 3.7 playing Pokemon and getting through 3 gym leaders. Our evals all focus on "immediate" intelligence, like the output, but that's for the chatbots usecase. Agents need to be able to operate independently for increasingly long periods of time; that'll be what makes AI autonomous and closer to the idea of a drop-in worker. It does seem that compute and context length might be a very big hurdle, especially if being able to stay coherent for hours requires exponentially more compute - I.e. a 5h task requires 100x more compute than a 30 min task. Though maybe not many tasks truly require 5 straight hours, instead they can be discretely broken down into multiple 30 min tasks. Still interesting and certainly stretches my timelines a little bit - proliferation is still probably around 5-10 years away at the earliest.